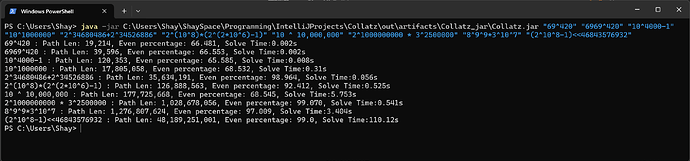

Full bulk solve output

Wow, that’s a really incredible algorithm, Shay! I was just batching the x3 and +1 operations into 128-bit accumulators so that the CPU did less math and read/wrote memory less often, but your recursive algorithm is on an entirely different level!

By accumulating the multiplications into enormous integers, you take advantage of the surprising fact that the asymptotic complexity of multiplying two n-bit integers isn’t O(n^2), but actually theoretically O(n log n)! Your solution is on an entirely different complexity class to mine! I think this is the first time I’ve ever seen sub-quadratic-time integer multiplication have a practical use!

I was able to recreate your algorithm in my Rust program, and though Rust’s big num library is seemingly not as efficient as Java’s (and it’s also not multithreaded), I was able to verify your submission:

Solving: (2^2^30 - 1) * 2^(5*10^11)

Solved in 11306.493 seconds

Path length: 514448571769

Even steps: 509274481258

Odd steps: 5174090510

Even ratio: 98.99%

I think the only improvements from here are to have more efficient big integer multiplication. Maybe a GPU-friendly algorithm? I could brush up on my CUDA ![]()

Also, I wonder if anyone else has figured out this algorithm for Collatz before… The only thing I could find was this paper from 2018: Collatz Conjecture for $2^{100000}-1$ is True - Algorithms for Verifying Extremely Large Numbers, viXra.org e-Print archive, viXra:1609.0374, which is nowhere near where we are:

The largest number verified for Collatz conjecture until now in the world is 2^100000-1, and this magnitude of extremely large numbers has never been verified. We discovered that this number can return to 1 after 481603 times of 3*x+1 computation, and 863323 times of x/2 computation.

Did we discover something new? ![]()

I’m curious if you can improve performance of Shay’s code by constructing some arbitrarily sized lookup table for the first n bits. It seems conceivable to me to have maybe a 24-bit lookup table containing the mult,add, and other necessary parameters. You could have your base recursion size to be the size of this table then, and avoid the actual compute and branches in the while loop. I don’t know if this would be better than actually doing the computation, but it seems interesting at the very least if it works.

I tried that and it was just slightly slower. The deeper parts of the computation are all memory limited, while the only CPU limited part is the larger multiplications. In java, at least.

The majority of time spent with Shay’s recursive solution is not in the base case, but doing the large multiplications when combining the two subproblems. Maybe it’s helpful if I describe thoroughly how Shay’s solution works.

Shay’s algorithm uses divide and conquer, a recursive approach that has one significant advantage over previous approaches, that I’ll describe a bit later.

The general solution

For this Collatz tracing algorithm, the idea is that we can operate on a chunk, say 32 bits of the input number. Whenever it is odd, we need multiply the whole number by 3 and add 1. However, since we are only seeing 32-bit of the potentially billion+ bits, we record the multiplication by 3 so that we can apply it later on every future chunk of the input number. This is called lazy or deferred evaluation. Additionally, this multiplication may overflow, and we need to track the overflow too. Thus we maintain two accumulators, which I call multiply and carry.

Whenever the number is even, we simply shift right by 1 bit. Of course, instead of actually shifting all billion+ bits, we can simply record how many bit shifts we are supposed to apply in another accumulator and delay the shift until we reach the next chunk. However, since this is by far the simplest step, I won’t mention it for the rest of this explanation. Likewise, we need additional logic to detect when we reach a final 1, and share that knowledge with future chunks, but I likewise won’t explain that part. And, I guess I should mention that if the input number has an infinite Collatz cycle… Well, let’s just say you’d instantly be famous and have bigger problems than trying to write a performant Collatz solver!

Okay, back to the algorithm. If the next step in tracing is odd, we multiply our number by 3 and add 1. We apply this to our 32-bit chunk (which may overflow again, which we can call new_carry), and for future chunks we have to record this in our accumulators. The correct formula for this is:

multiply *= 3

carry = 3 * carry + new_carry

Once we finish operating on this chunk, we return the carry and multiply as part of our solution to the subproblem. You could iterate through the rest of the chunks one by one using and updating these accumulators. The next chunk is multiplied by multiply and added by carry. Then we reset carry to 0 and start again.

This what my solution did. It’s fast for sure. But Shay took this to the next level with a crazy approach.

The recrusive algorithm

We can take a huge chunk of the input number and split it into two chunks. For the sake of this example, lets say both smaller chunks are n bits long. In practice it doesn’t have to match exactly.

The smaller n-bit chunk will generate its own multiply and carry that I described above, which we can rename small_multiply and small_carry. Both of these will be around n-bits in size.

The bigger n-bit chunk now needs to be adjusted. First we multiply it by small_multiply, then we add small_carry. (Again, both of these may overflow the n bits, so we can call the overflow carry_temp). Then we operate the Collatz algorithm on this n-bit chunk to retrieve big_multiply and big_carry.

We can then combine both sub results, including recording new multiply and carry accumulators. After operating on both chunks, the smaller multiplied the rest of the number by small_multiply, and the bigger multiplied the rest even more by big_multiply. We combine the carries too. The correct formula is:

multiply = small_multiply * big_multiply

carry = carry_temp * big_multiply + big_carry

Now if we implemented these multiplications naively (as in classic long multiplication), this algorithm would be just as fast as any other. Maybe even slower due to the constant allocation and deallocation of big numbers. But here’s the crazy part, the one advantage Shay’s algorithm has over the others! On small numbers, this multiplication is roughly O(n^2) complexity. But since we keep applying this algorithm recursively, we are using exponentially bigger small_multiply and big_multiply integers. Once we get to hundreds of thousands of bits, we can use more efficient multiplication algorithms that are closer to O(n log n)! If this sounds like black magic to you, that’s because it is. Read about the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm if you dare! Modern big integer libraries account for this, and if you look at their multiplication algorithms, they’re incredible beasts. In my case, the Rust num-bigint library uses Toom–Cook multiplication, which is approximately O(n^1.46) and thus has room for improvement at these scales.

Anyways, this merging of sub results, specifically the enormous multiplications, dominate the time complexity for big inputs (~99% of the compute time according to my performance profiles). This is in part thanks to how easy the base case is: simply run Collatz on a 32-bit integer and record the multiply and carry. Even if you doubled or tripled the speed of the base case, you’d speed up the algorithm by less than a percent.

This is why I’m currently exploring the idea of writing an efficient big integer multiplication algorithm for a GPU. ![]()

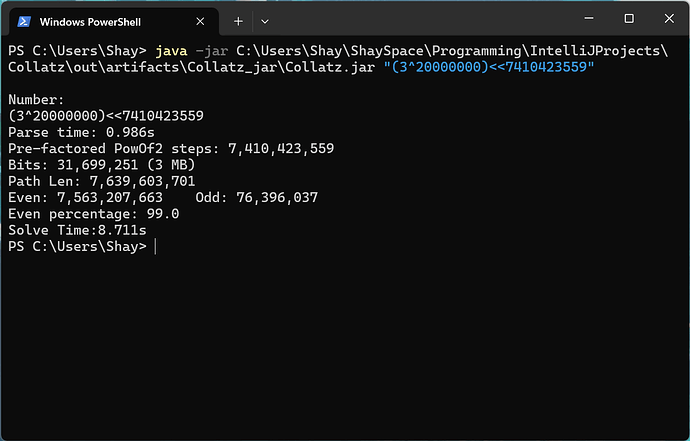

Java’s implementation is also tom cook, but my main goal was reduction of the number of large multiplications rather than than to take advantage of that speedup (although it’s certainly nice to be able to do so). Java can also use threading for large enough multiplications, but the speedup from that is not as significant as one would hope.

As far as how much time is spent where: using amd’s AMDuPROF profiler showed that mults accounted for half of the CPU time and where cpu bottlenecked (getting about 2.5 IPC), where the other half of all cpu time was memory bottlenecked (getting about 0.7 IPC). I’m assuming that many of the memory limitations would be alleviated by switching away from a garbage collected language & away from a big integer library that creates copies for every operation rather than being able to work in place.

Alright time to update

Took me a bit to work through it all (especially since the changes to some numbers was done on Discord rather than in the thread) but I think I’ve got it. If I missed any submissions or anything is wrong please let me know and I’ll update it.

The only potentially weird choice I think I made was to keep Fearless’ submission, but change the path length based on the 2 times it was run by someone else since it was a close value and otherwise valid as a submission. I also didn’t see anyone verify the 7.6b path (currently 3rd place).

Everything is ![]()

So I was able to implement the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm in Rust. The code still isn’t multithreaded, but it was able to verify 2^2^30-1 in about 2800 seconds. So I let it run overnight on a tougher problem.

Solving: 2^2^32 - 1

Solved in 20859.082 seconds

Path length: 57797126475

Even steps: 37099666003

Odd steps: 20697460471

Even ratio: 64.19%

I have since done some small optimizations and tweaks and re-ran it just to double check, though it looks like these tweaks didn’t help performance.

Solving: (2^2^32 - 1) * 4^10^12

Solved in 21838.181 seconds

Path length: 2057797126475

Even steps: 2037099666003

Odd steps: 20697460471

Even ratio: 98.99%

So (2^2^32 - 1) * 4^10^12 is my latest submission! If I want to go further, I could look into parallelizing the current code on the CPU. It looks like turning this into GPU-friendly code will be a lot more work…

These submissions are getting insane. We’re into the trillions of steps now.

time to bust out C and roll my own big ints

time to bust out C, write 1000000 lines of System Verilog, fabricate into a chip using silicon wafer, and run for fastest performance into astronomically large numbers of steps /j

This topic was automatically closed 90 days after the last reply. New replies are no longer allowed.